On the Architecture as Modification

Architecture as Modification -1Architecture as Modification

Working on the remodeling project for the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History, we had to ask ourselves a biggest critical question, "Why remodel?" The existing building had originally been the office of the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism since its initial completion, so that the task of remodeling it into a museum entailed many problems. The building was neither a designated cultural heritage, nor having any special quality other than its technical history of using the first flat plate system in Korea. Not surprisingly, "What should we preserve and what should we modify from this building?" became the key concern of design.

Remodeling means modifying and recycling what has existed. It requires the process of determining what is worth being recycled and what is not. That is to say, what has such a worth and what is dispensable? Some of our design team opined that it would be wiser to make a new construction radically, and many other contenders of the competition also proposed almost new constructions. In the process of gathering ideas for this project, we managed to establish the concrete concept of remodeling, the term which is now familiar to us. The following story is to ruminate more upon the profound meaning of remodeling.

Remodeling Defined to Fully Embody Architecture

According to the Building Act, remodeling refers to the "activity of major repair or partial extension to counteract the deterioration of or ameliorate the function of a building." Also, it is generally understood as "enhancing the real estate value of a building by improving its function and lifespan by extension, reconstruction, or major repair," or as "renovating an old apartment or townhouse while leaving the existing framework as it is." All in all, the term "remodeling" is often used as an interchangeable term with renovation, renewal, reform, or the like.

In a nutshell, remodeling signifies a recycling project in architecture, implying a wide range of meanings from maintenance to repair and alteration. It does not only mean a physical renewal, but also implies renewing the identity, use, character, and even profitability of a building. One of the general definitions mentioned above suggests that remodeling aims at enhancing the economical value of a building as a real estate, but here we intend to focus on the meanings and effects of remodeling as a way of embodying architecture, prior to the act of creating real estate incomes.

Reviewing the History of Remodeling

In recent days, the remodeling market is gradually expanding. An academic society and an architectural award about remodeling were established, along with the increase of the public interest. This expansion of interest in remodeling is above all due to the recent slowdown in the new construction sector, along with the deterioration of buildings which were constructed during the rapid growth period from the 1980s to 1990s. From a wider perspective, however, it can be ascribed to the substantial influence of modern architecture on which Korean architecture was based after the national independence and the Korean War.

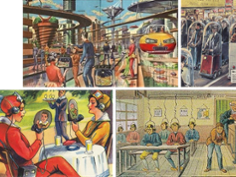

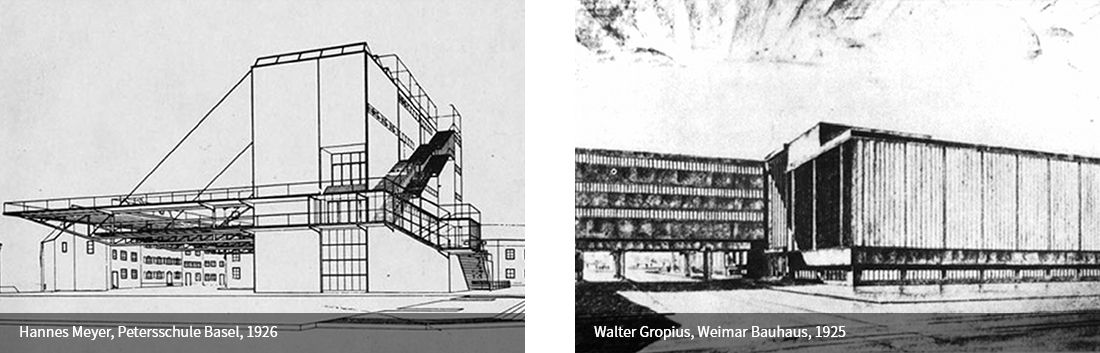

In general, modern architecture is classified as a style in architectural history. As defined by Le Corbusier, it is a style that often shows white and geometric forms excluding ornaments, overcoming the historicism and ornamentation of the nineteenth century and completing a new modernist aesthetics. This European modern architecture is seen to have become the matrix of internationalism in the process of propagating over the US. However, the early modern architecture was not limited to a style. It pursued functionalism as a way of social reform, aspiring for a modern utopia. The pioneers of modern architecture, such as Walter Adolph Georg Gropius and Hannes Meyer, had a clear consciousness of mission that architecture should be the foundation for the development of industrial civilization. They were enthusiastic about the huge growth in the early industrial era, giving a sublime meaning to the improvement of productivity. For them, the past was only the obstacle to overcome while architecture was a creation of the pure spirit producing the new. They believed the new was premised upon negating the old so as to replace the past. The endless development of industrial society in which they firmly believed as the most active exponents of modernization theory necessarily meant the complete break with and total destruction of the past.

Meanwhile, they rejected traditional academic norms by asserting that historical cities and villages should be converted into functional ones based on the logics of scientific thinking. Since then, the problems of "quantity" firstly emerged as a topic of architectural theory, such as how to secure housing for the urban workers whose number was rapidly increasing; the quantity of industrialized construction materials; and how to expand social infrastructure and public services. After all, the rapid growth and the problem of quantity can be seen to have characterized the modern era. As the public recognized the limits of growth which had seemed to be endless, modern architecture became criticized by the 1960s. As the threat of depleting natural and energy resources became real, it was inevitable to prepare countermeasures. Rather than stress production and growth, a new consciousness has arisen to reorganize what is existing, reuse the decrepit industrial complex, and regenerate the city.

Recognizing the Quality

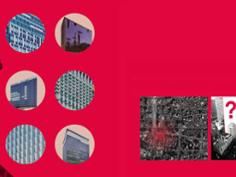

Korean society has pushed forward with industrial development and quantitative growth since the 1960s, while the structure of key industrial forces has rapidly changed time and again. The splendid growth and change left behind the byproducts of obsolescence in the shadows: decrepit factories, outdated housing in the hinterland, abandoned railroads and stations, and shut-down schools whose former students all left for the city.

These places should be treated differently by escaping the modernist thinking that espoused the myth of expansion and production. What have been left to us along with the memories of many people have special values which cannot be treated with the logic of production. The fact that they can serve as valuable architectural materials is what we have already been and now are realizing through the topical architectural events in recent days. Jongno Tower, built on the former site of Hwashin Department Store as the first of its kind in Korea, and the recently built Dongdaemun Design Plaza are having different reviews, and this means more careful approaches are needed to treat the weight and significance of history at the place. In an advanced society which has underwent the industrial process to some extent, the concept of richness is no longer defined only by material quantity. The meaning of richness is interpreted more diversely according to how much quality of service one can enjoy personally. This change of idea enables architects to have new questions:

“What is valuable and what should be conserved?”

“What should we hand down to our descendants?”

“What does heritage mean to us?”

The Value Criterion for Remodeling

Such questions as "Why preserve heritage?" or "Why don't we preserve some part of heritage?" stress that the value criterion of heritage conservation should be clearly applied. The criterion should never be set arbitrarily. "How should we give the meaning of heritage to a building?" The criterion would differ and vary culturally, so that it seems difficult to make it universal. In the 1960s to 70s, however, there was indeed an effort to establish the universal criterion that could apply to cultural heritage.

The Venice Charter

In May 1964, UNESCO held an international congress for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites in Venice, where the resolution was drafted and announced in the form of a charter, which is well known as the Venice Charter named after its venue. This charter has been widely used as the guidelines regarding heritage conservation to date. Its basic intent is as follows:

"Imbued with a message from the past, the historic monuments of generations of people remain to the present day as living witnesses of their age-old traditions. People are becoming more and more conscious of the unity of human values and regard ancient monuments as a common heritage. The common responsibility to safeguard them for future generations is recognized. It is our duty to hand them on in the full richness of their authenticity. It is essential that the principles guiding the preservation and restoration of ancient buildings should be agreed and be laid down on an international basis, with each country being responsible for applying the plan within the framework of its own culture and traditions."

It is true that the Venice Charter made much contribution to the preservation and restoration of historic remains. However, this charter has a limitation that is not universal but biased towards the European monumental buildings, i.e. inapplicable to those in non-European regions.

The Burra Charter

Recently emerging is a flexible concept of conservation which can be more easily and democratically engaged with, instead of the rigid frame of preservation by some professionals. In Australia, its own charter was announced as the Burra Charter which is applicable to the management of the national heritage on grounds of the international agreement and charter in 1979. Revised in 1981 and 1988 and substantially changed in 1999, this charter covers the contents about historical sites, objects, removal of heritage, new works like extension, use, structure, interference, and documentation, focusing on the natural and cultural scope of heritage. Also, it defines the fundamental concepts of heritage and cultural property according to the local characteristics, so that non-European countries as well seem to be able to apply the principle to their respective situations. The main concepts of this charter are as follows:

1) What places does it apply to?

It can be applied to "all types of places of cultural significance including natural, Indigenous and historic places with cultural values."

2) Why conserve?

"Places of cultural significance enrich people’s lives, often providing a deep and inspirational sense of connection to community and landscape, to the past and to lived experiences. They are historical records, that are important expressions of [the national] identity and experience. Places of cultural significance reflect the diversity of our communities, telling us about who we are and the past that has formed us and [our surrounding] landscape. They are irreplaceable and precious. These places of cultural significance must be conserved for present and future generations in accordance with the principle of inter-generational equity. The Burra Charter advocates a cautious approach to change: do as much as necessary to care for the place and to make it useable, but otherwise change it as little as possible so that its cultural significance is retained."

3) Cultural significance?

Cultural significance means the "aesthetic, historic, scientific, social, or spiritual value for past, present, or future generations." Unlike the Venice Charter, the Burra Charter takes the concept of "place" instead of "monument" because it is difficult to apply the concept of monumental buildings to the Australian indigenes who do not make structures sustainable for long time with natural materials. Australian indigenes value the natural environment in which a building sits more than the structure they build. Thanks to the concept of place, it became possible to apply the charter to every place with historical significance, be it with a building or not. Another point to notice in the Burra Charter is that it recognizes social values. Whereas the Venice Charter concentrates more on protecting the past aesthetic attitude of buildings, the Burra Charter recognizes that the contemporary social significance of place has cultural value as well, providing some solution for our question about the value criterion for remodeling.

Excerpts from "Architecture as Modification," Junglim Architecture Works 2014